One philosophy of Clean Architecture is to isolate framework for the application, so the framework won’t take over your application and you decide when and where to use them. In this application, I purposely not using any libraries at the beginning so I can have a better control on the project structure. Only after the whole application structure is laid out, I will consider replacing some components of the application with libraries. This way, the impact of introducing a framework or a library is isolated by the right dependency. Currently, I only used two libraries ozzo-validation¹ and YAML² besides logger, database, gRPC and Protobuf (which can’t be avoided), and all others are Go’s standard libraries.

You can use the project as the foundation to build your application upon. You may ask then the framework will take over the whole application, right? Yes, that is correct. The truth is that you need a basic framework as the foundation to build your application no matter it is home grown or a third party one. That foundation needs to have the right dependency and solid design in place, then you can decide whether to introduce other libraries or not. You surely can build one for yourself, but you probably will end up spending a lot of time and energy to make it solid. Instead of building your own, you can use this project as a starting point to save you a lot of effort.

The application container is the most complex piece of the project and is the key component to glue all different parts of the application together. The other parts of the project are straight forward and easy to understand, but not this one. The good news is once you understand this piece, then you get the whole application.

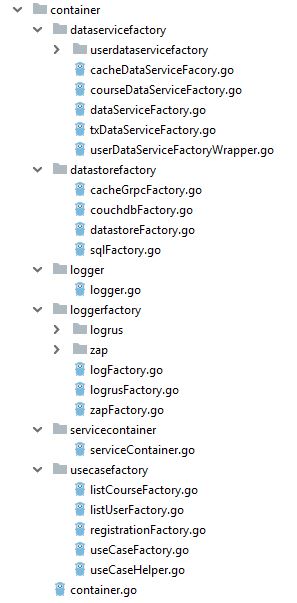

Components in “container” package:

There are 5 pieces in the container:

- The “container” package: it is responsible for creating concrete types and inject them into other files. There is only one file “container.go” in the top level package, and it has the interface for the container.

- The “servicecontainer” sub-package: Implementation of container interface. Only has one file “serviceContainer.go”, which is the key for “container” package. The following is the code. The starting point of it is “InitApp”, which reads configuration data from a file and set the logger.

|

|

- The “configs” sub-package: which is responsible for loading application configuration from a YAML file and save them into “appConfig” struct for container to use.

- The “logger” sub-package: It only has one file “logger.go” in it, which provides the logger interface and a “Log” variable to access the logger. Because every file needs logging, it deserves an independent package to avoid circular dependency.

- The last part are different type of factories.

They resemble the application layer. For the “usecase” and the “dataservice” layer, there are “usecasefactory” and “dataservicefactory”. Another factory is “datastorefactory”, which is responsible for creating the underline data handler. Because the provider of the data can be gRPC or other types of service besides databases, it is called “datastorefactry” not “databasefactory”. Logging component also has its own factory.

Use Case Factory:

For each use case, such as “registration” , the interface is defined in “usecase” package, but the concrete type is defined in “registration” sub-package under “usecase” package. Also, there is a factory in the container which is responsible to create the concrete use case instance. For the “registration” use case, it is “registrationFactory.go”. The relationship between the use case and the use case factory is one-to-one. And the use case factory is responsible for calling other factories to create the chain of concrete types needed. The lowest level concrete types are sql.DBs and gRPC connections that need to be passed to the persistence layer to access data.

If Go supports generic, you could create a generic builder to build different types of instance. Right now, I have to create one factory for each layer. The other option is using reflection, which I don’t like.

“Registration” Use Case Factory:

Each time a factory is called, it will build a new type.The following is the code that creates the concrete type for “registration” use case. It is the typical implementation of the factory method pattern. If you want to learn more about how the factory method pattern is implemented in Go, please see here³.

|

|

Data store factory:

“Registration” use case needs to access database through a handler, which is created by the data store factory. All code is in “datastorefactory” sub-package. I explained in detail how data store factory works in another “Dependency Injection”⁴.

Current implementation of the data store factory supports two databases, MySql and CouchDB, and a gRPC cache service; each implementation has it’s own factory file. If a new database is introduced, you just need to add a new factory file and add an entry in “dsFbMap” in the following code.

|

|

The following is the code for MySql database factory, which implemented “dsFbInterface” in above code. It creates the MySql database handler.

The container has a registry inside it to serve as a cache for things created by data store factory like a DB or a gRPC connection, which are only created once for the whole application. Whenever you need them, you first try to retrieve it from the registry, if not found, then create a new one and put it into the registry. That is what the following code did in the “Build” method.

|

|

Grpc Factory:

For “listUser” use case, it needs to call a gRPC Microservice (Cache service), and the factory is “cacheFactory.go”. Currently, all handlers of data service are created by the data store factory. The following is the code for gRPC factory for cache service. The “Build” method works very similar to the “SqlFactory”.

|

|

Logger factory:

Logger also has it’s own sub-package called “loggerfactory” and the structure is very similar to “datastorefactory” sub-package. “logFactory.go” has the logger factory builder interface and the map. Each individual logger has its own factory file. The following is the code for the log factory:

|

|

The following is the code for ZAP factory. It is similar to the data store factory. There is only one difference. Since logger-creation function is only called once, there is no need for the registry.

|

|

Configuration file:

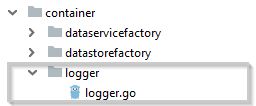

The configuration file gives you a overall idea of how the application is putting together:

The above image shows the first half of the file. The first section is the database config it supports; the second section is the Microservice with gRPC; the third section is the loggers it supports; the fourth section is the logger used by the app at run-time

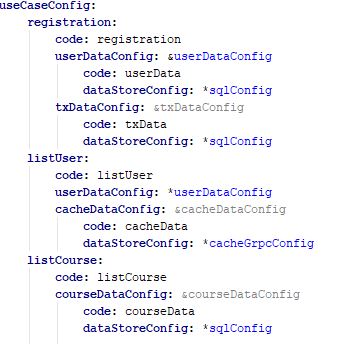

The following image shows the second half of the file. It lists all the use cases of the app and the data service that each use case needs.

What data should be saved in the config file?

Different components have different configuration items, some may have many such as loggers. We don’t need to save all configuration items in the configuration file, which can make it too big to manage. Usually we only need to save the options that need to be changed at run-time or those that can change value among different environments.

How is the design evolved?

The container seems to have a lot of stuff in it, the question is do we need all of them? We can certainly simplify it if you don’t need all features. When I first created it, it is quite simple and I kept adding functionalities to it and eventually it took the current form.

When it is started, I was just thinking to use the factory method pattern to create concrete types and there is no logging, no configuration files, no registry.

I started with the use case and the data store factory. Initially, for each use case, a new database handler is created, which is not ideal. So, I added a registry to cache all connections to make sure they are only created once.

Then I found (I got some inspiration from here⁵) it is better to put all the configuration information in a file, so I can change it without changing the code. I created a YAML file (appConfig[type].yaml) and “appConfig.go” to load the content from the file into an application configuration struct-“appConfig” and pass it to factory builders. The “[type]” can be “prod”, “dev”, “test” and so on. The config file is loaded only once. Currently, it didn’t use any third party lib, but I am thinking to switch to Vipe⁶ in the future, so it can support dynamic reloading of application configurations from a configuration server. To make the switch, I only need to change one file, “appConfig.go”.

For logging, I’d like only one instance of logger so I can set the same logging configurations for the whole application. I created a logger package inside the container. I also tried different logging libraries to figure out which one is the best, then I created a logging factory to make it easier to add new loggers in the future. Please read “application logging”⁷ for detail.

Source Code:

The complete code is in github: https://github.com/jfeng45/servicetmpl

Other articles:

Please read the rest of the articles in this series in “Go Microservice with Clean Architecture”.

Reference:

[1] ozzo-validation

[2] YAML support for the Go language

[4]Go Microservice with Clean Architecture: Dependency Injection

[5] How I pass around shared resources (databases, configuration, etc) within Golang projects

[6]viper

[7]Go Microservice with Clean Architecture: Application Logging

Translations

See also

- Go Microservice with Clean Architecture: Dependency Injection

- Go Microservice with Clean Architecture: Coding Style

- Go Microservice with Clean Architecture: Transaction Support

- Go Microservice with Clean Architecture: Application Design

- Go Microservice with Clean Architecture: Design Principle